Some economists worry that uncontrolled inflation will soon surface following the money printing antics of the central bankers. Still others believe that deflation will arise instead. So what to make of this contentious issue? If economists themselves can't agree on how a major situation will unfold, can we dummies, with no formal learning in economics, be more prescient than them? Worry not, you only need to know a little bit about money to trump them. Once you understand money, you can easily grasp the cause of inflation, hyperinflation and deflation. For this post, we'll deal with inflation to be followed by deflation in the next post. As we are dealing with the real world, our lodestar to understanding money is economic history, not economic theory which is good only for the surreal world.

To know what money is, you don't need to rely on the economists' M measures, i.e., M0 to M3 or sometimes M4. Same goes for the velocity of money, a crackpot idea that should have never seen the light of day. Those are red herring measures which serve more to distract than illuminate. The only measure that should be used is total credit. Credit is money. In fact between 95% and 98% of money is credit except in a hyperinflationary environment wherein physical money will drown credit. So under normal conditions the physical bills in your pocket don't make a dent to the money supply.

Economists who fear unconstrained money printing by central bankers are exposing their money ignorance (See "Money 101 for the Fed"). How much cash do you carry on your body or stash under your pillow? Compare that with the amount you keep in the bank and invest in bonds. If the cash that you keep in its physical form is more that 5% of your total cash holdings, you belong to the 1%, at the bottom, that is. Your cash in the bank is not sitting there idle. The bank will lend it to someone. So instead of tallying the cash, you can get the same effect by looking from the opposite angle, that is, the amount of credit drawn by the various borrowers. However credit from the bank is only one element of the total credit in the system. Credit also arises from bonds issued by corporations, municipalities and the government.

What about the newfangled financial instruments, such as the alphabet soup of derivatives? No need to feel overwhelmed. Their only impact is to make credit widely available. They don't reduce the risk though they may lower the price, i.e., the interest rate, of credit because more money now gets to the market and the cost of the intermediary, that is, the bank has been eliminated.

However money is only one of the causes of inflation. Recall the 4C framework of currency, capacity, consumption and communication. In simple terms, if the goods or services production lags the supply of currency, the result is inflation (see left panel of left picture). In rare circumstances, goods or services production may decline at a faster rate than that of money supply; that also leads to inflation (see right panel of the same picture). Another combination which only Robert Mugabe can magically conjure is a fast climbing money supply accompanied by a declining goods or services production. This is hyperinflation. Note that hyperinflation is a state in which price increases are experienced daily while inflation monthly. Hyperinflation disastrously disrupts an economy that only insane politicians would allow it to proceed indefinitely.

What drives the movement of each component of the 4C? The supply of goods or services is dependent on advances in capacity and communication. Every Kondratieff Wave has witnessed a significant leap in both capacity and communication, resulting in lesser input for greater output. Even now a disruption in either capacity or communication could drive costs or prices up. The recent Pakistani blockade of the border crossings along the Afghan-Pakistan border has driven the cost of delivering fuel to NATO's remote outposts to US$400 a gallon.

The supply of money on the other hand depends on the increase in credit unless we talk of hyperinflation which requires the government to print money and spend it. However in most true representative democracies, it's not possible for governments to create hyperinflation because there are enough checks and balances to constrain their budgets. Only autocratic government can foster hyperinflation. Weimar Germany, the post WWI German government, although democratically elected, was different because of its unique circumstances which will be explained later.

Direct borrowings by businesses that bypass the bank usually through corporate bonds cannot be blamed for contributing to inflation. A non-financial business is restricted in the level of debt that it can raise relative to its capital, this proportion being termed the gearing or leverage. A gearing of 3 to 4 would have been the maximum tolerable for a non-financial business. Financial corporations however have a tremendous ability to create credit or money. Usually, they could push the ratio to 15 although the excessive risk takers among them have stretched this ratio to the extreme limits, with disastrous consequences. The gearing of Long-Term Capital Management which succumbed in 1998 skyrocketed to 292 (including total derivatives) or 62.5 (based on assumed risk only), while in the 2008 failures of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, they were having ratios of around 35 and 31. The financial corporation thus are the obvious culprits for any inflation fostered by excess money supply.

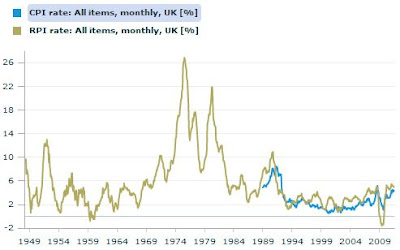

So the rule for inflation in most modern democracies is this: for normal inflation, it is always caused by increased financial institution lending, not government printing unless it is hyperinflation in which case, the culprit will always be the government. But excessive lending need not necessarily lead to inflation if the goods and services production capacity can match the increased money supply. As is typical of any 60-year Kondratieff Wave cycle (see left chart from The Economist for the fourth wave which began in 1960), the first half of the wave is always plagued with capacity constraint but the second half is blessed with capacity surplus. So even though there may be pockets of inflation during the second half, they are mainly due to short-term inelastic supply of certain goods, such as houses and oil. Their prices are doomed to fall when the capacity bottleneck is broken. A similar portrayal of the inflation chart of the third Kondratieff Wave for the period 1900-1960 however would not appear so clear cut as the two world wars distorted the inflation numbers.

As for consumption, since the start of the Industrial Revolution, it has been benign because population growth has always been growing or at least hasn't faltered. But that's about to change with the fourth Kondratieff wave. The entry of women into the labour force has escalated the opportunity cost of raising kids. Women's total fertility rate (TFR) is falling all over the world, in some places, such as Japan, even below replacement rates. Population declines mean that consumption would now count far more towards contributing to deflation (less goods consumed means more goods available at a given money supply).

Although consumption now struggles, capacity flourishes. It is obvious now that we need less manpower to achieve a given level of production. What happens to the unneeded manpower? In the past, they could move from agriculture to industry or migrate to the new world of the Americas. Even up to the third Kondratieff Wave, manufacturing was still employing many workers. That enabled many to move up to middle class status. That has now changed as technology has automated many tasks while globalisation, aided by containerisation, has offshored tasks requiring many workers to foreign countries with cheap labour. Those in middle class now are being demoted to lower class, worsening the wealth and income gap between the upper and the lower class.

One more issue that has been confusing us is whether inflation is cost-push or demand-pull. Generally, since the Industrial Revolution it's been demand-pull as mankind's ingenuity has enabled it to break the supply constraints. On occasions, when cost-push arose, the situation wouldn't last long, meaning round about 10 years. Take the 1973 oil crisis. The oil prices jumped then because the producers hadn't been exploring for new oil fields as prices had remained low despite the increasing demand. We've been fed the story of how Paul Volcker tamed the inflation in 1981 by hiking the interest rates to more than 19%. That's a half-truth. If Volcker had been Fed Chairman in 1974, his action would have needlessly put a great number of people out of work for a prolonged period. Luckily it was the early 1980s because by then the oil producers' spare capacity was reaching record highs, so the convulsions wrought on the economy by the sky high interest rates didn't last long. Compare this with the oil price hike that pushed oil to more US$140 per barrel in July 2008. That didn't have much ripple effect on the inflation numbers simply because of excess capacity in goods and services production. The goods and services producers had to absorb the higher energy costs and soldier on with wafer thin margins.

Let's get to the hyperinflationary world of Weimar Germany to see why it happened and why it wasn't a disaster it had been made out to be. In reality it was a relatively short-lived episode lasting from July 1922 to November 1923 but has been given too much bad press and wrongly accused of fostering the rise of Hitler. The cause of the hyperinflation was money printing by the German government during World War I. To finance war spending, the German government issued bonds which were subscribed fully by the Reichsbank through the issuance of new notes. These notes then circulated through the economy. However rationing and price controls during the war postponed the consumption of goods and price inflation. After the war the new socialist government increased spending to pay for higher wages and compensate displaced war victims at a time when capacity was still constrained. Prices rose but then stabilised after February 1920. The government however continued printing money. Prices held steady until May 1921 before continuing their rise, finally erupting into hyperinflation in July 1922.

Wasn't it easy to kill off hyperinflation and if so, why did the German government continued with its money printing madness? It actually was but the German economy then was burdened by war reparations which amounted to US$64 billion in gold. Had Germany paid the war reparations, its currency would have depreciated and the economy would in time regain its competitiveness, given the industriousness of the German people. But after a string of defaults by Germany in its war reparation payments, France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr in January 1923. In response, Germany printed more money to pay the companies, that suffered from the occupation, and their evicted workers. This was the trigger that unleashed the hyperinflation. However by November 1923, the hyperinflation was subdued through the replacement of the much devalued Papiermark by the Rentenmark at the rate of 1 trillion Papiermark for 1 Rentenmark, which was in turn replaced by the Reichsmark the following year. The reparation payments were rescheduled to more manageable terms. The sum was eventually reduced to US$29 billion in 1929. Money from abroad to invest in the stabilised German economy especially from the US provided support for the Reichsmark.

How bad the impact of the hyperinflation, it didn't lead to the rise of Hitler. Hitler attempted a coup d'état only in November 1923, about the time the hyperinflation was tamed. If hyperinflation was the villain, Hitler's popularity would have plummeted right after his failed coup d'état. To be sure, the conditions in Germany during the inflationary years were chaotic with lots of violence but that was to be expected of a losing combatant which had lost territories and had war reparations to settle.

However such conditions paled in comparison with the economic depression that afflicted Germany beginning in late 1929. This time the German economy instead of being flushed with money as in the hyperinflationary years was now short of funds as the Americans had pulled out their money for more profitable stock market speculation on Wall Street. Export markets dried up and banks were hit with closures. In 1932, the year before Hitler's ascent, Germany's unemployment rate was 25%. These negative conditions smoothened Hitler's rise and his eventual consolidation of power.

So which is worse, hyperinflation or deflation? Surely it's deflation. The conditions we're in now are ideal for a deflationary environment. The economists who have been warning us about the danger of money printing and hyperinflation very soon have to eat humble pie as prices data all over the world are pointing towards lower inflation. It won't be long before deflation rear its ugly head and these very same economists will be warning of deflationary dangers instead.

With so much confusion in economics and politics, it's high time that we step back and view events from a new perspective - the perspective of pattern recognition. Recognitia derived from recognition and ia (land), signifies an environment in which pattern recognition prevails in the parsing of events and issues, and in the prognostication of future outlook.

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Charles de Gold

'Tis the season to be protesting. Day by day, as more countries are being sucked into the vortex of protest, it's opportune to reexamine another protest movement, this time the one that rocked France in 1968. The US had suffered from protests since 1965 supposedly arising from disaffection with the Vietnam war. Yet similar outbreaks in many European cities in 1968 had nothing to do with the Vietnam war. Of all such protests, the most violent was reserved for France.

It's also fitting that the French president then was Charles de Gaulle, its first president under the Fifth Republic. He led the writing of the Fifth Republic's constitution which transformed the parliamentary system of the Fourth Republic into a strong executive presidential system, one that fits De Gaulle's personality. De Gaulle once said, "A true leader always keeps an element of surprise up his sleeve, which others cannot grasp but which keeps his public excited and breathless." How true. Read the biographies of most strong leaders, you'll find that they relish in keeping their populace guessing as to their true intentions and actions. Except when it comes to economics, because in true poetic justice fashion, it is economics that keeps the leaders guessing for answers. And invariably the answers always elude them.

De Gaulle was soon to find out how easy it was to be outwitted by economics. On the last day of 1967, he addressed his countrymen, "It is impossible to see how France today could be paralysed by crises as she has been in the past." It was a bit premature. 1968 was to be the year of protest movements. Till today nobody knows why the wave of protests erupted in 1968. The stock answer has always been youth rebellion, a sort of culture issue that leaves more questions than answers.

We've seen how a similar movement in the United States had been triggered by slowing income growth that was addressed only through higher female labour force participation rate (LFPR) which impact was felt from the 1970s onwards. Without the high female LFPR, real income, instead of stabilising, might have been deteriorating. The benefit of the high female LFPR has now run its course. As the LFPR keeps drooping, real household income will surely follow suit. Those not participating in the labour force will be willing fodder for the barricades.

There was one common economic theme between the 1960s and our present times, to wit, the low inflationary environment. Everybody loves low inflation unaware that low inflation benefits creditors more than debtors. As the economy forges ahead over time, there'll be more debtors relative to creditors. If no structural changes arise, the ownership of wealth will be heavily skewed, favouring the creditors at the expense of debtors. It'll take a barrage of violent agitations to knock some sense into the politicians, prodding them to change course by tolerating high inflation and curtailing free trade and free capital movement.

Like the US, France enjoyed a prolonged period of economic prosperity right after World War II. That's why de Gaulle was blindsided by the protests. However he had been reelected for a second term in 1965 by a narrow margin. That should have signalled him that dangerous times were just around the corner. Money was becoming short in supply. It was still the era of Bretton Woods in which fixed exchange rates ruled.

Although the US was still notching current account surpluses then, its balance of payments were registering deficits because of the direct investment in European countries by its corporations. Nowadays the US current account is in heavy deficit but instead of the foreigners offsetting the deficits with long-term investment in the US, they are buying short-term bonds which give them the smug feeling of increased wealth. So either way, when the US current account was in surplus or is in deficit, the foreigners have been benefitting from US money.

Towards the late 1960s, the US were suffering from declining gold reserves. President Johnson attempted to limit the outflow of gold first by having a voluntary restriction on overseas investment in 1965 and when this didn't work, a mandatory one in 1968. Both had temporary effects as the overvalued US dollar was the cause of the gold outflow. The French franc was similarly overvalued. De Gaulle wrongheadedly believed in the gold standard and the benefits of a strong currency. In fact he had been calling for the price of gold to be increased to $70 per ounce to spite the US.

It is not surprising then that the protest started in May 1968 with students at the University of Nanterre. It then spread to workers who were demanding for higher wages. As the wages demand was met, the economy became more uncompetitive without a franc devaluation. Capital flight ensued. De Gaulle survived the 1968 riots but not a referendum the following year in which he had staked his presidency. He resigned from office in April 1969.

The currency shortage was eventually resolved by a 12% devaluation by his successor, Georges Pompidou in August 1969, four months after De Gaulle's resignation. De Gaulle may have foresight in political and military matters - he was one of the first among the French generals to appreciate the significance of the third generation mobile mechanised warfare that was eventually employed by the German army - but his weakness in grasping economic issues was to eventually lead to his downfall. Though he was an upright person who believed strongly in the virtue of savings, in politics, honesty and prudence don't make for a brilliant statesman.

Now more than 40 years have passed since the violent protests. Yet the current crop of EU leaders have learned nothing from the mistakes of De Gaulle. They are repeating the same errors and sharing the same perverted beliefs held by De Gaulle, that almost brought France to its knees in 1968. Only that this time it's not only France that will bear the brunt of the upheaval but the whole House of Europe, paving the way for its eventual collapse.

It's also fitting that the French president then was Charles de Gaulle, its first president under the Fifth Republic. He led the writing of the Fifth Republic's constitution which transformed the parliamentary system of the Fourth Republic into a strong executive presidential system, one that fits De Gaulle's personality. De Gaulle once said, "A true leader always keeps an element of surprise up his sleeve, which others cannot grasp but which keeps his public excited and breathless." How true. Read the biographies of most strong leaders, you'll find that they relish in keeping their populace guessing as to their true intentions and actions. Except when it comes to economics, because in true poetic justice fashion, it is economics that keeps the leaders guessing for answers. And invariably the answers always elude them.

De Gaulle was soon to find out how easy it was to be outwitted by economics. On the last day of 1967, he addressed his countrymen, "It is impossible to see how France today could be paralysed by crises as she has been in the past." It was a bit premature. 1968 was to be the year of protest movements. Till today nobody knows why the wave of protests erupted in 1968. The stock answer has always been youth rebellion, a sort of culture issue that leaves more questions than answers.

We've seen how a similar movement in the United States had been triggered by slowing income growth that was addressed only through higher female labour force participation rate (LFPR) which impact was felt from the 1970s onwards. Without the high female LFPR, real income, instead of stabilising, might have been deteriorating. The benefit of the high female LFPR has now run its course. As the LFPR keeps drooping, real household income will surely follow suit. Those not participating in the labour force will be willing fodder for the barricades.

There was one common economic theme between the 1960s and our present times, to wit, the low inflationary environment. Everybody loves low inflation unaware that low inflation benefits creditors more than debtors. As the economy forges ahead over time, there'll be more debtors relative to creditors. If no structural changes arise, the ownership of wealth will be heavily skewed, favouring the creditors at the expense of debtors. It'll take a barrage of violent agitations to knock some sense into the politicians, prodding them to change course by tolerating high inflation and curtailing free trade and free capital movement.

Like the US, France enjoyed a prolonged period of economic prosperity right after World War II. That's why de Gaulle was blindsided by the protests. However he had been reelected for a second term in 1965 by a narrow margin. That should have signalled him that dangerous times were just around the corner. Money was becoming short in supply. It was still the era of Bretton Woods in which fixed exchange rates ruled.

Although the US was still notching current account surpluses then, its balance of payments were registering deficits because of the direct investment in European countries by its corporations. Nowadays the US current account is in heavy deficit but instead of the foreigners offsetting the deficits with long-term investment in the US, they are buying short-term bonds which give them the smug feeling of increased wealth. So either way, when the US current account was in surplus or is in deficit, the foreigners have been benefitting from US money.

Towards the late 1960s, the US were suffering from declining gold reserves. President Johnson attempted to limit the outflow of gold first by having a voluntary restriction on overseas investment in 1965 and when this didn't work, a mandatory one in 1968. Both had temporary effects as the overvalued US dollar was the cause of the gold outflow. The French franc was similarly overvalued. De Gaulle wrongheadedly believed in the gold standard and the benefits of a strong currency. In fact he had been calling for the price of gold to be increased to $70 per ounce to spite the US.

During the same period, both the British and French were also losing competitiveness as a result of slower productivity growth. Britain had been suffering from large current account deficits that made sustaining a strong pound untenable. To stem the loss of reserves, British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson devalued the pound by 14 percent on 18 November 1967 from $2.80 to $2.40. The Bank of England had earlier in the day spent ₤200m worth of gold and dollar reserves trying to shore up the pound. The devaluation did improve Britain's economy and reduce its current account deficits. By 1969, its balance of payment recorded a surplus although in the 1970s, Britain continued to fall back to deficits because of the oil crisis coupled with stubbornly low productivity.

De Gaulle however refused to countenance such a move. Being a prudent man, he was also stinting in public spending, refusing to invest on education, roads, telecommunication, housing and social services. In his private life, he took great pains to separate his official from personal expenses, which he paid out of his own pocket. As can be seen in the chart below (from Reinhart and Rogoff), in the 1960s, the French government was reducing its share of spending as a proportion of GDP. A more accurate measure would be total debt as a percentage of GDP but such a measure for France in the 1960s is not available on the web.

France was thus suffering from a shortage of currency. Its government was reducing its relative spending while at the same time, its corporations were having problems with their export markets as a result of the overvalued franc.

De Gaulle however refused to countenance such a move. Being a prudent man, he was also stinting in public spending, refusing to invest on education, roads, telecommunication, housing and social services. In his private life, he took great pains to separate his official from personal expenses, which he paid out of his own pocket. As can be seen in the chart below (from Reinhart and Rogoff), in the 1960s, the French government was reducing its share of spending as a proportion of GDP. A more accurate measure would be total debt as a percentage of GDP but such a measure for France in the 1960s is not available on the web.

France was thus suffering from a shortage of currency. Its government was reducing its relative spending while at the same time, its corporations were having problems with their export markets as a result of the overvalued franc.

It is not surprising then that the protest started in May 1968 with students at the University of Nanterre. It then spread to workers who were demanding for higher wages. As the wages demand was met, the economy became more uncompetitive without a franc devaluation. Capital flight ensued. De Gaulle survived the 1968 riots but not a referendum the following year in which he had staked his presidency. He resigned from office in April 1969.

The currency shortage was eventually resolved by a 12% devaluation by his successor, Georges Pompidou in August 1969, four months after De Gaulle's resignation. De Gaulle may have foresight in political and military matters - he was one of the first among the French generals to appreciate the significance of the third generation mobile mechanised warfare that was eventually employed by the German army - but his weakness in grasping economic issues was to eventually lead to his downfall. Though he was an upright person who believed strongly in the virtue of savings, in politics, honesty and prudence don't make for a brilliant statesman.

Now more than 40 years have passed since the violent protests. Yet the current crop of EU leaders have learned nothing from the mistakes of De Gaulle. They are repeating the same errors and sharing the same perverted beliefs held by De Gaulle, that almost brought France to its knees in 1968. Only that this time it's not only France that will bear the brunt of the upheaval but the whole House of Europe, paving the way for its eventual collapse.

Monday, December 5, 2011

The protests, 45 years on

In October 1965, a protest movement took root in the US. It was to last until the US began its pullout from Vietnam in 1973. The received wisdom on its cause has always been the sudden increase in draft or conscription numbers for the war. Some commentators believed that the advent of same day broadcasting and cheap video tape energised the protests. Now with a bit of help from the web, we can carry out a forensic autopsy on the protest movement to discover the true reasons for the widespread and prolonged convulsions the US has ever experienced on its own soil.

Discovering the root cause is the first step towards understanding the severity of the 1960s protests. More meaningfully, we'd want to know why the protests then died down after the early 1970s. Knowing the real pattern is useful because that pattern will be our guide for appreciating the current occupy protests that are shaking at the core of the Western civilisation.

As protests are usually linked to economic crises, the US GDP (see chart below from Forbes magazine) is a good subject to start with. The period 1965-1970 was characterised by plummeting GDP ending in the 1970 recession. Growth picked up post-1970 especially after Nixon broke the fixed link between the US dollars and gold in August 1971. Two years later, it dropped again as a result of the oil price surge following the OPEC embargo. The surprising thing is that there have been no widespread protests since despite the occasional episodes of falling GDP, in some cases much worse than the late 1960s. That is, till now.

Remember that during this time the US was still having a current account surplus (see right panel of the chart below from The Economist), albeit with a declining rate, so the foreign countries couldn't have supplied the goods either to meet the demand from the higher money supply.

Even the US industrial production was running above capacity throughout the second half of the 1960s (see graph below from The New York Times). So goods and services supply were tight, thus the inflationary conditions. But inflation couldn't have been the main culprit since in later years under Gerald Ford's and Jimmy Carter's watch, during which the protests no longer resurfaced, the inflation rate was much worse.

The 1960s was also the beginning of the fourth Kondratieff wave. It would have been impossible for the growth drivers (computers and internet) of this wave to have kicked in at such an early stage. After eliminating all suspects, we are left with only one. It is the one that enabled the US to get out of the economic doldrums of the late 1960s and early 1970s. But its contribution has not been given the credit to which it richly deserves. It is the increased female participation in the labour force. And the driver that enabled the women to enter the labour force in great numbers was electricity, the main engine of the third Kondratieff wave.

Electricity-enabled home appliances which began to enter the market in 1930s to 1950s allowed women to have more free time. So by the mid-1960s, the women started to enter the labour force in large numbers to supplement the income of their spouses. But the overall impact was felt only from the 1970s since the inclining women labour force participation rate (LFPR) outweighed the declining male LFPR only then (see graph below). As household income increased, the urge to protest declined.

The impact of the roughly 8% higher LFPR was significant, not only because the productive capacity increased but also the consumption ability grew. However after the drivers of the fourth Kondratieff wave entered the economy in a big way - computers in the 1980s and internet in the 1990s - the LFPR began to flag. The new drivers make it possible to run operation with a greatly reduced number of workers than before. Globalisation worsened the already bad situation. Capacity swelled as foreign countries became part of the supply chain. Initially inflation was a scourge because certain commodities, in particular oil, had a lag of 7 to 10 years to come onstream. Well the new oil fields are now ready to be tapped at a time money supply is fast shrinking with massive debt write-offs. The world will be awash with cheap goods but bereaved of money.

Worse, the high female LFPR is producing a backlash since population growth is also decreasing as women have reduced their fertilility rate (see chart on the left). Our ability to consume the plentiful goods produced has thus been severely depleted. Now you know why the protesters have taken to the streets. What they need now is a strong galvanising cause. In the 1960s, it was the Vietnam war. The Afghan war pales in comparison as the number of soldiers fighting is relatively very small. That leaves the Wall Street and the top 1% of the wealth owners. But nobody knows who are in that group and nobody wants to claim to be in it either. An amorphous target is not a valid cause. We don't know what the eventual cause will be but the one thing that we can surely expect is that the protests are going to turn more violent.

As protests are usually linked to economic crises, the US GDP (see chart below from Forbes magazine) is a good subject to start with. The period 1965-1970 was characterised by plummeting GDP ending in the 1970 recession. Growth picked up post-1970 especially after Nixon broke the fixed link between the US dollars and gold in August 1971. Two years later, it dropped again as a result of the oil price surge following the OPEC embargo. The surprising thing is that there have been no widespread protests since despite the occasional episodes of falling GDP, in some cases much worse than the late 1960s. That is, till now.

The mass protest movement has now begun to rear its ugly head not only in the US but throughout the world. What drives people to join forces in voicing out their grievances in the open? Not once but repeatedly and simultaneously in places far distant from each other. Surely there must be a unifying cause but behind that cause there must exist a social tension that galvanises the protesters. And what better catalyst to fuel that tension than economic anxieties and difficulties.

The 1950s and 1960s were probably the most economically prosperous period in US history. In fact it would have been the longest US economic expansion had not a 10-month recession in 1960 interrupted the relentless growth. The rise of the protest movement towards the end of the period was therefore totally unexpected and hasn't been plausibly explained. In most written accounts on the protests, the generally agreed upon cause is the Vietnam war. Yes the Vietnam war is the plausible cause but the real cause lies much deeper. A true understanding of the 1950s and 1960s decades are called for. A look at the Fed funds rate (see chart from Wikipedia below) immediately tells of the difficulties that the US was facing in the later half of the 1960s.

Up until August 1971, the dollar was the primary anchor currency under the Bretton Woods monetary system in which its value was fixed at US$35 per ounce of gold. This meant the US economy would increasingly become more uncompetitive as other currencies could be devalued relative to the dollar. The gold outflow was a strong sign of this uncompetitiveness as speculators were betting that the dollar would fall. The inherent weakness of the dollar was reflected in the free market price of gold which in 1968 was trading at $41 per ounce. To stem this fall, the Fed funds rate had to be steadily increased peaking at 9.19% in August 1969. Contrast this to the previous 20 years in which the rate had never exceeded 4%.

President Johnson's spending on the Vietnam war and Great Society - mainly Social Security and healthcare - started to creep up from 1966. However it was the expansion of credit for business corporations and households that had been fueling the economy prior to Johnson's escalated spending. As inflation inched up in 1966, the Fed raised the Fed funds rate to 5.76% by November 1966, slowing the economy in the process though Johnson's public spending prevented the economy from falling into recession.

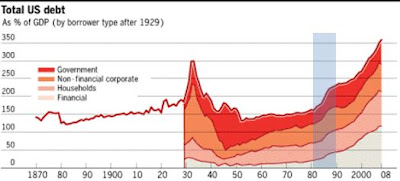

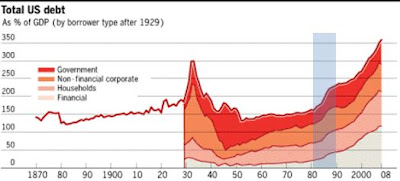

The impact can be seen in the money supply measure, the best being the total credit market debt (see chart below) instead of the generally accepted M1, M2 or M3. In 1966, 1968 and 1969, the total credit relative to GDP was lower compared to the three years preceding 1966. This was the primary cause of the 1970 recession much as the contraction in 1960-61 had contributed to the recession of those years.

But the economic difficulties were not evident from the unemployment rate as seen in the misery index (see chart below). Yet the inflation rate was increasing despite the slowdown in debt growth. Obviously there must be something that had been constraining capacity reducing its ability to match the debt growth, even though now subdued.

President Johnson's spending on the Vietnam war and Great Society - mainly Social Security and healthcare - started to creep up from 1966. However it was the expansion of credit for business corporations and households that had been fueling the economy prior to Johnson's escalated spending. As inflation inched up in 1966, the Fed raised the Fed funds rate to 5.76% by November 1966, slowing the economy in the process though Johnson's public spending prevented the economy from falling into recession.

The impact can be seen in the money supply measure, the best being the total credit market debt (see chart below) instead of the generally accepted M1, M2 or M3. In 1966, 1968 and 1969, the total credit relative to GDP was lower compared to the three years preceding 1966. This was the primary cause of the 1970 recession much as the contraction in 1960-61 had contributed to the recession of those years.

But the economic difficulties were not evident from the unemployment rate as seen in the misery index (see chart below). Yet the inflation rate was increasing despite the slowdown in debt growth. Obviously there must be something that had been constraining capacity reducing its ability to match the debt growth, even though now subdued.

Remember that during this time the US was still having a current account surplus (see right panel of the chart below from The Economist), albeit with a declining rate, so the foreign countries couldn't have supplied the goods either to meet the demand from the higher money supply.

Even the US industrial production was running above capacity throughout the second half of the 1960s (see graph below from The New York Times). So goods and services supply were tight, thus the inflationary conditions. But inflation couldn't have been the main culprit since in later years under Gerald Ford's and Jimmy Carter's watch, during which the protests no longer resurfaced, the inflation rate was much worse.

The 1960s was also the beginning of the fourth Kondratieff wave. It would have been impossible for the growth drivers (computers and internet) of this wave to have kicked in at such an early stage. After eliminating all suspects, we are left with only one. It is the one that enabled the US to get out of the economic doldrums of the late 1960s and early 1970s. But its contribution has not been given the credit to which it richly deserves. It is the increased female participation in the labour force. And the driver that enabled the women to enter the labour force in great numbers was electricity, the main engine of the third Kondratieff wave.

Electricity-enabled home appliances which began to enter the market in 1930s to 1950s allowed women to have more free time. So by the mid-1960s, the women started to enter the labour force in large numbers to supplement the income of their spouses. But the overall impact was felt only from the 1970s since the inclining women labour force participation rate (LFPR) outweighed the declining male LFPR only then (see graph below). As household income increased, the urge to protest declined.

The impact of the roughly 8% higher LFPR was significant, not only because the productive capacity increased but also the consumption ability grew. However after the drivers of the fourth Kondratieff wave entered the economy in a big way - computers in the 1980s and internet in the 1990s - the LFPR began to flag. The new drivers make it possible to run operation with a greatly reduced number of workers than before. Globalisation worsened the already bad situation. Capacity swelled as foreign countries became part of the supply chain. Initially inflation was a scourge because certain commodities, in particular oil, had a lag of 7 to 10 years to come onstream. Well the new oil fields are now ready to be tapped at a time money supply is fast shrinking with massive debt write-offs. The world will be awash with cheap goods but bereaved of money.

Worse, the high female LFPR is producing a backlash since population growth is also decreasing as women have reduced their fertilility rate (see chart on the left). Our ability to consume the plentiful goods produced has thus been severely depleted. Now you know why the protesters have taken to the streets. What they need now is a strong galvanising cause. In the 1960s, it was the Vietnam war. The Afghan war pales in comparison as the number of soldiers fighting is relatively very small. That leaves the Wall Street and the top 1% of the wealth owners. But nobody knows who are in that group and nobody wants to claim to be in it either. An amorphous target is not a valid cause. We don't know what the eventual cause will be but the one thing that we can surely expect is that the protests are going to turn more violent.

Friday, November 25, 2011

Tripped by the Phillips curve

The link between unemployment and inflation once used to move according to a predictable relationship as mapped on what is known as the Phillips curve (PC) (see chart on the left). The curve was named after Bill Phillips (1914-1975), a New Zealand economics professor, who had observed wage inflation and unemployment rates in Britain in earlier decades. The negative sloping curve reflects the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment: a rise in one is accompanied by a fall in the other. This relationship held out in the 1960s.

By 1970, the relationship started to give in (see the left-hand panel of the chart below). Even Milton Friedman came up with his own hypothesis on unemployment, which is the straight line Long Range Phillips Curve (LRPC), as seen in the above chart. By the subsequent decades, the relationship went haywire (see right-hand panel below). The Economist even devoted an article, "Heroes of the zeroes", whence I've sourced the charts in this post, on the Phillips curve.

Another way of presenting the relationship between inflation and unemployment is the Misery Index chart from Bloomberg (see below). Looked from this perspective, it is obvious that there's no relationship whatsoever between the two even as early as the 1920s and 1930s. Most economists are good at rationalising events which would have been easily disproved had they been more discerning with their observations.

By 1970, the relationship started to give in (see the left-hand panel of the chart below). Even Milton Friedman came up with his own hypothesis on unemployment, which is the straight line Long Range Phillips Curve (LRPC), as seen in the above chart. By the subsequent decades, the relationship went haywire (see right-hand panel below). The Economist even devoted an article, "Heroes of the zeroes", whence I've sourced the charts in this post, on the Phillips curve.

Another way of presenting the relationship between inflation and unemployment is the Misery Index chart from Bloomberg (see below). Looked from this perspective, it is obvious that there's no relationship whatsoever between the two even as early as the 1920s and 1930s. Most economists are good at rationalising events which would have been easily disproved had they been more discerning with their observations.

Bill Phillips's observations either were flawed or he had restricted them to those years which had conformed to his hypothesis. Those were the days when globalisation and technological change were minimal. Once these conditions were gone, the politicians would in time lose control of the economy. One thing leads to another. It's no wonder that they are now losing control of politics. Once the horse has bolted, closing the gate now is useless. It's time for the politicians themselves to bolt because the public has no more trust in them. Those crafty enough have seduced the technocrats to stick their necks out in order to save the politicians' necks.

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Clinton's ingenious disingenuity

Mark Twain used to quip, "It is better to keep your mouth shut and appear stupid than to open it and remove all doubt." Bill Clinton however has refused to do so. He has been bragging about his four years of budget surpluses in his new book, "Back to Work: Why We Need Smart Government for a Strong Economy", that also dishes out nostrums for reviving the economy. He certainly has credibility based on the US economic performance, as reflected by the decreasing rates of inflation and unemployment, while he was in office (see chart below from Bloomberg).

That is true only if you believe that the economy depends solely on the decisions and actions of the President and his administration. But the economy is much more than that. Many variables are in play, all of which are best explained by the 4C framework. We can pick just two of those variables, that is, capacity and communication, to provide the basis for the improving economy under Clinton's watch. And both of them had nothing to do with what Clinton did during his administration. Instead, they were predictable aspects of the fourth Kondratieff Wave.

The capacity of that wave can be attributed to the computer, especially the microprocessor. But capacity alone won't unleash investment unless that capacity can be communicated to a wider group of users and producers. The internet, which started to come into widespread use in the 1990s, provides the answer to that missing variable. So Clinton, being lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time, reaped the rewards of the wave's technological progress.

As the wave was on the rise, it was natural for business investment to roll along, in a too bullish fashion, eventually ending in the dotcom bust in March, 2000. Consequently prior to the bust, that is, throughout the latter half of the 1990s, the debt of the financial, business and household sectors was briskly expanding (see left chart from The Economist). The period under Clinton's watch is marked red on the chart. The expansion enabled the government to pare down its debt resulting in four years of consecutive budget surpluses. The US government could save because the others borrowed. Yet the total debt was on the rise. Now should Clinton shoulder the blame for not controlling the debt growth? Certainly but looking at the chart, the biggest offenders were Reagan and Bush, Jr.

Another chart, on the left, also from The Economist provides the reason for the continuing credit expansion during the second Bush administration. Under Clinton's watch, the fed funds rate never dropped below 4% except at the beginning of his administration when the economy was still recovering from the 1990-91 recession. Because of the bullish sentiment following the internet technological revolution, credit expansion was not constrained by the relatively high interest rates. The expectation of better economic prospects deluded businesses into investing in ventures that had no hopes of economic returns.

After the dotcom bust, the Fed lowered the interest rate in the hope of continuing the economic growth. This time, however, the credit expansion was undertaken by the households who borrowed for capital gains and equity drawdown. Again, without any hope of matching returns from rental income, the situation turned from a housing bubble into a debacle.

Clinton's pontification on how to turn around the economy should thus be taken with a pinch of salt. If he doesn't understand the factors that contributed to his budget surpluses, you shouldn't expect him to comprehend the real causes of the current recession. If you really want to get to the root of the current crisis, read up economic history rather than the policy nostrums of a self-deceived ex-president.

That is true only if you believe that the economy depends solely on the decisions and actions of the President and his administration. But the economy is much more than that. Many variables are in play, all of which are best explained by the 4C framework. We can pick just two of those variables, that is, capacity and communication, to provide the basis for the improving economy under Clinton's watch. And both of them had nothing to do with what Clinton did during his administration. Instead, they were predictable aspects of the fourth Kondratieff Wave.

The capacity of that wave can be attributed to the computer, especially the microprocessor. But capacity alone won't unleash investment unless that capacity can be communicated to a wider group of users and producers. The internet, which started to come into widespread use in the 1990s, provides the answer to that missing variable. So Clinton, being lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time, reaped the rewards of the wave's technological progress.

As the wave was on the rise, it was natural for business investment to roll along, in a too bullish fashion, eventually ending in the dotcom bust in March, 2000. Consequently prior to the bust, that is, throughout the latter half of the 1990s, the debt of the financial, business and household sectors was briskly expanding (see left chart from The Economist). The period under Clinton's watch is marked red on the chart. The expansion enabled the government to pare down its debt resulting in four years of consecutive budget surpluses. The US government could save because the others borrowed. Yet the total debt was on the rise. Now should Clinton shoulder the blame for not controlling the debt growth? Certainly but looking at the chart, the biggest offenders were Reagan and Bush, Jr.

Another chart, on the left, also from The Economist provides the reason for the continuing credit expansion during the second Bush administration. Under Clinton's watch, the fed funds rate never dropped below 4% except at the beginning of his administration when the economy was still recovering from the 1990-91 recession. Because of the bullish sentiment following the internet technological revolution, credit expansion was not constrained by the relatively high interest rates. The expectation of better economic prospects deluded businesses into investing in ventures that had no hopes of economic returns.

After the dotcom bust, the Fed lowered the interest rate in the hope of continuing the economic growth. This time, however, the credit expansion was undertaken by the households who borrowed for capital gains and equity drawdown. Again, without any hope of matching returns from rental income, the situation turned from a housing bubble into a debacle.

Clinton's pontification on how to turn around the economy should thus be taken with a pinch of salt. If he doesn't understand the factors that contributed to his budget surpluses, you shouldn't expect him to comprehend the real causes of the current recession. If you really want to get to the root of the current crisis, read up economic history rather than the policy nostrums of a self-deceived ex-president.

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Rise by the oil, fall by the oil (Part 2)

The first phase of Thatcher's administration (1979-1983) succeeded in subduing inflation even though total debt, i.e., money, grew. Inflation thus is not only a function of monetary growth but also of energy costs, primarily, oil. However the inflation fight was at the expense of the unemployment rate (see chart below from Paul Maunders blog) which remained stubbornly high.

Thatcher had to get the unemployment rate down to provide evidence of success for her economic policies. The easiest way to achieve growth was to unleash credit but first, Friedman's monetarism theory of stable monetary growth had to be permanently ended. The Bank of England did its part by officially abandoning monetarism in 1986. The US government had already turned on the monetary tap in 1984, thus securing Reagan his second term.

Thatcher had to get the unemployment rate down to provide evidence of success for her economic policies. The easiest way to achieve growth was to unleash credit but first, Friedman's monetarism theory of stable monetary growth had to be permanently ended. The Bank of England did its part by officially abandoning monetarism in 1986. The US government had already turned on the monetary tap in 1984, thus securing Reagan his second term.

Back to Thatcher, in her second term, she accomplished several noteworthy achievements. First she managed to break the back of the trade unions when the coal miners' union gave up their strike in March 1985. She also carried out large scale privatisation of nationalised industries. Estimates of the privatisation proceeds have ranged from £19 billion to £29 billion.

However in 1986 the monetary value of Britain's oil production collapsed following Saudi's price war to spite the non-OPEC interlopers. Without the backing of the oil wealth, Thatcher had nothing to show for all the hardships of monetarism induced inflationary busting. So something had to be done not only fast but fast enough to bear fruit before the next election. The base interest rate was the tool: from a high of 14% in January 1985, it bottomed out at 7.5% by May 1988 (see chart above from www.houseweb.co.uk).

Her earlier privatisation of the nationalised industries and enfeeblement of the trade unions were expected to boost productivity which would unleash the goods supply to match the increased credit supply. This would also reduce unemployment just in time for the next election. Theoretically, that was how it should work but in reality, Britain's goods production had been severely impaired through neglect that the only growth for the economy was in the financial services and non-tradable real estate sectors. The eclipse of manufacturing was not entirely due to Thatcher's earlier contractionary monetary policy; the British firms had failed to invest at the same pace as Germany's or Japan's. Furthermore, Britain's petro economy had fostered a strong currency that remained so until early 1985, making exports non-competitive for its manufactured goods.

The credit growth that lasted from 1986 to 1990 was emblematic of Thatcher's trial-and-error experiment with the British economy. Her accomplice in this scheming was her Chancellor, Nigel Lawson who dismantled all financial barriers and regulations with the 1986 Big Bang. Lawson also brought down the basic tax rate from 30% in 1986 to 25% by 1988 and the top rate from 60% to 40%.

Thatcher and Lawson opened the gate for the foreign banks to set up shop in London much as the developing countries wooed the goods producers from the developed world to establish factories on their soil. It was hoped that financial services would take over from manufacturing as the country's biggest economic driver and turn London into a global financial centre. However, financial services could never replace the goods exports lost to the new manufacturing upstarts from Asia. The above chart from www.economicshelp.org proves that Britain has never been able to regain her manufacturing competitiveness that was lost way back in the early 1980s. It was estimated then that financial services exports would have to increase by 10% to make up for a 1% drop in manufactured goods exports.

Banking unlike manufacturing however is a very dangerous game. In manufacturing, during a recession, a major producer that packs up and closes shop will disrupt only the local supply chain and employment. In financial services, because of the widespread lending between financial institutions, a failure of a major bank can pull down the others unless the government steps in to take over the debts. This wholesale crash will cause the money supply to collapse and seize up the economy.

It is true that currently a large share of the assets, i.e., loans disbursed, of the British banks not only are made abroad but are also supported by borrowings from abroad: Table 9D of the Bank of International Settlement statistics as of 30 June 2011 shows that foreign banks' claims on UK borrowers amounted to US$3.06 trillion (second only to the US) while British banks' claims on foreign borrowers totalled US$4.18 trillion (biggest in the world). Regardless, the aphorism, attributed to J. Paul Getty, that when you borrow small, the problem is yours, but when you borrow big, the problem is the bank's, rings true for Britain's debt situation. Given this disproportionate dependency of the British economy on financial services (see how much the yawning current account goods deficit gap was closed by financial services in the above chart), Thatcher's promotion of financial services will in time come home to roost in the coming Grand Depression.

But Thatcher herself didn't have to wait for the coming Grand Depression. The quick-fix boost to the economy enabled Thatcher to be elected for a third term in 1987. Britain's house ownership at around 70% ranked among the world's highest, making the public eager voters for Thatcher's Conservative party. However the good times would soon be over, marking her third term as her downfall phase. The easy money had resulted in a capacity constraint that was followed by a surge in Britain's current account deficits and higher inflation (see chart above). To subdue inflation, the base rate was doubled from 7.5% in May 1988 to 15% by October 1989, bursting the housing bubble. Unemployment crept up to its pre-boom level. However inflation took two years after the peak of the interest rate hike, to be contained. Worse, with the oil prices still in the doldrums, Thatcher no longer had the luxury of oil wealth to appease the public with increased social security and unemployment benefits.

The trap had been set for Thatcher to stumble into. It just needed only a trigger. She survived the poll tax riots in March 1990. But the general unfavourable economic conditions made it tougher for her to ride roughshod over her Tory colleagues without creating deep animosity. They needed a bone to pick with her. Her strident stand against increasing European encroachment on Britain's sovereignty became their cause. Feeling that she might lose the second round of a leadership challenge, she voluntarily resigned her premiership in November 1990. What an ignominious exit, three consecutive wins at the polls, only to be stabbed in the back by party colleagues.

Had Thatcher restricted herself to two terms, like Reagan, she would have stepped down with her reputation held in high esteem. The British public would be now yearning for her leadership although in reality, she benefited largely from factors beyond her control, especially the oil wealth. Without its crutch, her downfall was predictably swift.

Thatcher had to get the unemployment rate down to provide evidence of success for her economic policies. The easiest way to achieve growth was to unleash credit but first, Friedman's monetarism theory of stable monetary growth had to be permanently ended. The Bank of England did its part by officially abandoning monetarism in 1986. The US government had already turned on the monetary tap in 1984, thus securing Reagan his second term.

Thatcher had to get the unemployment rate down to provide evidence of success for her economic policies. The easiest way to achieve growth was to unleash credit but first, Friedman's monetarism theory of stable monetary growth had to be permanently ended. The Bank of England did its part by officially abandoning monetarism in 1986. The US government had already turned on the monetary tap in 1984, thus securing Reagan his second term.

Unfortunately I've not been able to find the chart that plots the 1986 credit increase for the UK. The best that I've got is the earlier chart shown in Part 1 of this story which ends in 1985. Its follow-up chart (see below, also McKinsey's) however begins from 1987, leaving a gap for 1986. Regardless we can interpolate to find out what transpired in 1986. The UK's total credit as at end 1985 was slightly below 150% of GDP while that for (probably end) 1987 was 189 percent. So within two years, credit as a percentage of GDP grew by around 40 percent. That is a blistering pace that would have rocket-propelled any economy. The other thing about the chart that strikes the eye is the relentless growth in credit up until the onset of the current crisis. That strongly explains why Tony Blair, like Thatcher, also managed to hang on to three terms. One thing for sure, the successive British governments have been running the country into the ground as the price for keeping up with the major powers. The mess has now dropped into David Cameron's lap who is certain to be overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the total debt level.

Back to Thatcher, in her second term, she accomplished several noteworthy achievements. First she managed to break the back of the trade unions when the coal miners' union gave up their strike in March 1985. She also carried out large scale privatisation of nationalised industries. Estimates of the privatisation proceeds have ranged from £19 billion to £29 billion.

Her earlier privatisation of the nationalised industries and enfeeblement of the trade unions were expected to boost productivity which would unleash the goods supply to match the increased credit supply. This would also reduce unemployment just in time for the next election. Theoretically, that was how it should work but in reality, Britain's goods production had been severely impaired through neglect that the only growth for the economy was in the financial services and non-tradable real estate sectors. The eclipse of manufacturing was not entirely due to Thatcher's earlier contractionary monetary policy; the British firms had failed to invest at the same pace as Germany's or Japan's. Furthermore, Britain's petro economy had fostered a strong currency that remained so until early 1985, making exports non-competitive for its manufactured goods.

The credit growth that lasted from 1986 to 1990 was emblematic of Thatcher's trial-and-error experiment with the British economy. Her accomplice in this scheming was her Chancellor, Nigel Lawson who dismantled all financial barriers and regulations with the 1986 Big Bang. Lawson also brought down the basic tax rate from 30% in 1986 to 25% by 1988 and the top rate from 60% to 40%.

Thatcher and Lawson opened the gate for the foreign banks to set up shop in London much as the developing countries wooed the goods producers from the developed world to establish factories on their soil. It was hoped that financial services would take over from manufacturing as the country's biggest economic driver and turn London into a global financial centre. However, financial services could never replace the goods exports lost to the new manufacturing upstarts from Asia. The above chart from www.economicshelp.org proves that Britain has never been able to regain her manufacturing competitiveness that was lost way back in the early 1980s. It was estimated then that financial services exports would have to increase by 10% to make up for a 1% drop in manufactured goods exports.

Banking unlike manufacturing however is a very dangerous game. In manufacturing, during a recession, a major producer that packs up and closes shop will disrupt only the local supply chain and employment. In financial services, because of the widespread lending between financial institutions, a failure of a major bank can pull down the others unless the government steps in to take over the debts. This wholesale crash will cause the money supply to collapse and seize up the economy.

It is true that currently a large share of the assets, i.e., loans disbursed, of the British banks not only are made abroad but are also supported by borrowings from abroad: Table 9D of the Bank of International Settlement statistics as of 30 June 2011 shows that foreign banks' claims on UK borrowers amounted to US$3.06 trillion (second only to the US) while British banks' claims on foreign borrowers totalled US$4.18 trillion (biggest in the world). Regardless, the aphorism, attributed to J. Paul Getty, that when you borrow small, the problem is yours, but when you borrow big, the problem is the bank's, rings true for Britain's debt situation. Given this disproportionate dependency of the British economy on financial services (see how much the yawning current account goods deficit gap was closed by financial services in the above chart), Thatcher's promotion of financial services will in time come home to roost in the coming Grand Depression.

But Thatcher herself didn't have to wait for the coming Grand Depression. The quick-fix boost to the economy enabled Thatcher to be elected for a third term in 1987. Britain's house ownership at around 70% ranked among the world's highest, making the public eager voters for Thatcher's Conservative party. However the good times would soon be over, marking her third term as her downfall phase. The easy money had resulted in a capacity constraint that was followed by a surge in Britain's current account deficits and higher inflation (see chart above). To subdue inflation, the base rate was doubled from 7.5% in May 1988 to 15% by October 1989, bursting the housing bubble. Unemployment crept up to its pre-boom level. However inflation took two years after the peak of the interest rate hike, to be contained. Worse, with the oil prices still in the doldrums, Thatcher no longer had the luxury of oil wealth to appease the public with increased social security and unemployment benefits.

The trap had been set for Thatcher to stumble into. It just needed only a trigger. She survived the poll tax riots in March 1990. But the general unfavourable economic conditions made it tougher for her to ride roughshod over her Tory colleagues without creating deep animosity. They needed a bone to pick with her. Her strident stand against increasing European encroachment on Britain's sovereignty became their cause. Feeling that she might lose the second round of a leadership challenge, she voluntarily resigned her premiership in November 1990. What an ignominious exit, three consecutive wins at the polls, only to be stabbed in the back by party colleagues.

Had Thatcher restricted herself to two terms, like Reagan, she would have stepped down with her reputation held in high esteem. The British public would be now yearning for her leadership although in reality, she benefited largely from factors beyond her control, especially the oil wealth. Without its crutch, her downfall was predictably swift.

Monday, October 31, 2011

Rise by the oil, fall by the oil (Part 1)

We've seen how Ronald Reagan benefited from the drop in oil prices (see "Great in debt") to secure a presidential second term. Margaret Thatcher, his political soul mate, also profited from oil but in a contrasting fashion. It's doubtful whether they were aware how their fortunes had been closely tied to swings in oil prices.

Oil's tentacles go beyond deciding the fates of petro-state politics. Even great leaders of the western world survived on the indulgence of oil. Had Reagan been in Carter's shoes, he would have faced the same travails that had plagued Carter with equally limited options of wriggling out. Reagan avoided the fate of Carter because oil prices were trending downwards towards the end of his first term as a result of falling consumption following the long recession from July 1981 to November 1982. The cause was the high contractionary interest rates imposed by Volcker. To his benefit, oil prices stayed low throughout the second term of his administration. This time it was the Saudis who precipitated the price fall by suddenly unleashing output from two million barrels per day (mbpd) to five mbpd.

Reagan's successor George Bush the first might have earned his second term had he not raised taxes and had the Savings and Loan financial institutions not imploded, the implosion itself a consequence of Reagan's deregulation. These two events resulted in a pullback of the money supply growth, effectively scuttling Bush's reelection hopes. The oil price then wasn't a spoiler as its price was still benign except for a short-lived spurt as a result of the first Gulf War.

Thatcher's fortunes however differed. Whereas the US presidents needed cheap oil for economic prosperity, Thatcher depended on expensive oil to sustain Britain which was gradually losing competitiveness on its manufacturing front. Thatcher's predecessor, James Callaghan correctly predicted that the winner of the 1979 election would stay in office for a long time, reaping the benefits of the oil revenues which were about to pour in. He didn't need any clairvoyance as Britain's North Sea oil which had been first discovered in the early 1970s was subject to the usual lead time of 7 to 10 years from discovery to production (see chart above). Thatcher came in at the right time to hold the premiership for more than 11 years.

Now oil has always been subject to great price swings. So were Thatcher's fortunes. The significant drop in oil production and exports in the early 1990s (see left chart) correlated with Thacher's resignation from the premiership on 28 November 1990.

Now oil has always been subject to great price swings. So were Thatcher's fortunes. The significant drop in oil production and exports in the early 1990s (see left chart) correlated with Thacher's resignation from the premiership on 28 November 1990.

So it appears that Thatcher's great standing rested entirely on oil. How about her economics ideology which initially relied on Milton Friedman's monetarism? She was said to have successfully tamed inflation. Like the oil story, we can set the record straight since most people still think that defeating inflation is a matter of just hiking the interest rates up. Friedman would have recommended restricting the supply of credit rather than manipulating its price, that is, the interest rate, but Friedman's approach would have caused a sudden shock to the credit supply that all developed economies have now abandoned it.

Thatcher, although a novice at economics, was a consummate politician, ever willing to ditch any economic ideologies at the first sign of voters' discontent, particularly nearing an election year. Unfortunately, the British public had to become guinea pigs for her Friedman-influenced monetarist ideas. To suppress inflation, she started off not only by raising interest rates to 17% in 1980 but also drastically reducing public spending in her first budget. The impact was immediate. By the following year manufacturing production fell by 14% and unemployment rose to 2.7 million. British manufacturing capacity shrunk by 25% in 1979-81. Not only that, influenced by Friedman's Chicago liberalism doctrine, she also abolished the controls on capital movement. This is one measure that all countries will come to regret 30 years later with the onset of the Grand Depression.

The austerity measures were driving Britain into bankruptcy. Only the North Sea oil was keeping Britain solvent. Soon Thatcher became the most unpopular Prime Minister in British history. Unemployment hit the Black minorities disproportionately, eventually boiling over into the summer 1981 race riots in several British cities. Thatcher quickly reversed course by ditching Friedman's monetarism temporarily. It is sad to find that politicians, including Britain's very own David Cameron, still believe in austerity measures when history has proven them to be a complete failure.

By autumn 1981, Thatcher started cutting interest rates. In the following year's budget, Thatcher increased public expenditure. With the high number of the unemployed, it was not surprising that inflation remained low. Oil prices were also moving downwards. More importantly, the British economy was increasing its money supply (see chart below from McKinsey). It should also be noted that the previous British governments since the World War II had to contend with high public sector debt. So they resorted to inflation to bring the share of public debt down to manageable level. Thatcher benefited greatly from her predecessors' efforts, enabling her to start pumping credit again, though this time using households and financial institutions to undertake the borrowings. This recovery and the euphoria from the Falklands war victory enabled Thatcher to retain her premiership in the 1983 election.

Oil's tentacles go beyond deciding the fates of petro-state politics. Even great leaders of the western world survived on the indulgence of oil. Had Reagan been in Carter's shoes, he would have faced the same travails that had plagued Carter with equally limited options of wriggling out. Reagan avoided the fate of Carter because oil prices were trending downwards towards the end of his first term as a result of falling consumption following the long recession from July 1981 to November 1982. The cause was the high contractionary interest rates imposed by Volcker. To his benefit, oil prices stayed low throughout the second term of his administration. This time it was the Saudis who precipitated the price fall by suddenly unleashing output from two million barrels per day (mbpd) to five mbpd.

Reagan's successor George Bush the first might have earned his second term had he not raised taxes and had the Savings and Loan financial institutions not imploded, the implosion itself a consequence of Reagan's deregulation. These two events resulted in a pullback of the money supply growth, effectively scuttling Bush's reelection hopes. The oil price then wasn't a spoiler as its price was still benign except for a short-lived spurt as a result of the first Gulf War.

Thatcher's fortunes however differed. Whereas the US presidents needed cheap oil for economic prosperity, Thatcher depended on expensive oil to sustain Britain which was gradually losing competitiveness on its manufacturing front. Thatcher's predecessor, James Callaghan correctly predicted that the winner of the 1979 election would stay in office for a long time, reaping the benefits of the oil revenues which were about to pour in. He didn't need any clairvoyance as Britain's North Sea oil which had been first discovered in the early 1970s was subject to the usual lead time of 7 to 10 years from discovery to production (see chart above). Thatcher came in at the right time to hold the premiership for more than 11 years.

Now oil has always been subject to great price swings. So were Thatcher's fortunes. The significant drop in oil production and exports in the early 1990s (see left chart) correlated with Thacher's resignation from the premiership on 28 November 1990.

Now oil has always been subject to great price swings. So were Thatcher's fortunes. The significant drop in oil production and exports in the early 1990s (see left chart) correlated with Thacher's resignation from the premiership on 28 November 1990.So it appears that Thatcher's great standing rested entirely on oil. How about her economics ideology which initially relied on Milton Friedman's monetarism? She was said to have successfully tamed inflation. Like the oil story, we can set the record straight since most people still think that defeating inflation is a matter of just hiking the interest rates up. Friedman would have recommended restricting the supply of credit rather than manipulating its price, that is, the interest rate, but Friedman's approach would have caused a sudden shock to the credit supply that all developed economies have now abandoned it.

Thatcher, although a novice at economics, was a consummate politician, ever willing to ditch any economic ideologies at the first sign of voters' discontent, particularly nearing an election year. Unfortunately, the British public had to become guinea pigs for her Friedman-influenced monetarist ideas. To suppress inflation, she started off not only by raising interest rates to 17% in 1980 but also drastically reducing public spending in her first budget. The impact was immediate. By the following year manufacturing production fell by 14% and unemployment rose to 2.7 million. British manufacturing capacity shrunk by 25% in 1979-81. Not only that, influenced by Friedman's Chicago liberalism doctrine, she also abolished the controls on capital movement. This is one measure that all countries will come to regret 30 years later with the onset of the Grand Depression.

The austerity measures were driving Britain into bankruptcy. Only the North Sea oil was keeping Britain solvent. Soon Thatcher became the most unpopular Prime Minister in British history. Unemployment hit the Black minorities disproportionately, eventually boiling over into the summer 1981 race riots in several British cities. Thatcher quickly reversed course by ditching Friedman's monetarism temporarily. It is sad to find that politicians, including Britain's very own David Cameron, still believe in austerity measures when history has proven them to be a complete failure.

By autumn 1981, Thatcher started cutting interest rates. In the following year's budget, Thatcher increased public expenditure. With the high number of the unemployed, it was not surprising that inflation remained low. Oil prices were also moving downwards. More importantly, the British economy was increasing its money supply (see chart below from McKinsey). It should also be noted that the previous British governments since the World War II had to contend with high public sector debt. So they resorted to inflation to bring the share of public debt down to manageable level. Thatcher benefited greatly from her predecessors' efforts, enabling her to start pumping credit again, though this time using households and financial institutions to undertake the borrowings. This recovery and the euphoria from the Falklands war victory enabled Thatcher to retain her premiership in the 1983 election.

The impact of the inflation especially in the 1970s helped to whittle down the real value of debt. As seen in the chart below (again from McKinsey), debt or credit has always been on the increase. Any political leaders thinking of crimping the total credit growth are dangerously courting a total social breakdown. Only inflation could ameliorate a debt growth. Consequently, the inexorable rise in UK's total real debt level beginning from the Thatcher's administration can be attributed not in a small way to the low inflation conditions prevailing since then.

Since Thatcher's story has many interesting lessons for our bumbling EU politicians, we'll continue the second part of the story with the conditions leading to her downfall.

Monday, October 10, 2011

Great in debt