Oil's tentacles go beyond deciding the fates of petro-state politics. Even great leaders of the western world survived on the indulgence of oil. Had Reagan been in Carter's shoes, he would have faced the same travails that had plagued Carter with equally limited options of wriggling out. Reagan avoided the fate of Carter because oil prices were trending downwards towards the end of his first term as a result of falling consumption following the long recession from July 1981 to November 1982. The cause was the high contractionary interest rates imposed by Volcker. To his benefit, oil prices stayed low throughout the second term of his administration. This time it was the Saudis who precipitated the price fall by suddenly unleashing output from two million barrels per day (mbpd) to five mbpd.

Reagan's successor George Bush the first might have earned his second term had he not raised taxes and had the Savings and Loan financial institutions not imploded, the implosion itself a consequence of Reagan's deregulation. These two events resulted in a pullback of the money supply growth, effectively scuttling Bush's reelection hopes. The oil price then wasn't a spoiler as its price was still benign except for a short-lived spurt as a result of the first Gulf War.

Thatcher's fortunes however differed. Whereas the US presidents needed cheap oil for economic prosperity, Thatcher depended on expensive oil to sustain Britain which was gradually losing competitiveness on its manufacturing front. Thatcher's predecessor, James Callaghan correctly predicted that the winner of the 1979 election would stay in office for a long time, reaping the benefits of the oil revenues which were about to pour in. He didn't need any clairvoyance as Britain's North Sea oil which had been first discovered in the early 1970s was subject to the usual lead time of 7 to 10 years from discovery to production (see chart above). Thatcher came in at the right time to hold the premiership for more than 11 years.

Now oil has always been subject to great price swings. So were Thatcher's fortunes. The significant drop in oil production and exports in the early 1990s (see left chart) correlated with Thacher's resignation from the premiership on 28 November 1990.

Now oil has always been subject to great price swings. So were Thatcher's fortunes. The significant drop in oil production and exports in the early 1990s (see left chart) correlated with Thacher's resignation from the premiership on 28 November 1990.So it appears that Thatcher's great standing rested entirely on oil. How about her economics ideology which initially relied on Milton Friedman's monetarism? She was said to have successfully tamed inflation. Like the oil story, we can set the record straight since most people still think that defeating inflation is a matter of just hiking the interest rates up. Friedman would have recommended restricting the supply of credit rather than manipulating its price, that is, the interest rate, but Friedman's approach would have caused a sudden shock to the credit supply that all developed economies have now abandoned it.

Thatcher, although a novice at economics, was a consummate politician, ever willing to ditch any economic ideologies at the first sign of voters' discontent, particularly nearing an election year. Unfortunately, the British public had to become guinea pigs for her Friedman-influenced monetarist ideas. To suppress inflation, she started off not only by raising interest rates to 17% in 1980 but also drastically reducing public spending in her first budget. The impact was immediate. By the following year manufacturing production fell by 14% and unemployment rose to 2.7 million. British manufacturing capacity shrunk by 25% in 1979-81. Not only that, influenced by Friedman's Chicago liberalism doctrine, she also abolished the controls on capital movement. This is one measure that all countries will come to regret 30 years later with the onset of the Grand Depression.

The austerity measures were driving Britain into bankruptcy. Only the North Sea oil was keeping Britain solvent. Soon Thatcher became the most unpopular Prime Minister in British history. Unemployment hit the Black minorities disproportionately, eventually boiling over into the summer 1981 race riots in several British cities. Thatcher quickly reversed course by ditching Friedman's monetarism temporarily. It is sad to find that politicians, including Britain's very own David Cameron, still believe in austerity measures when history has proven them to be a complete failure.

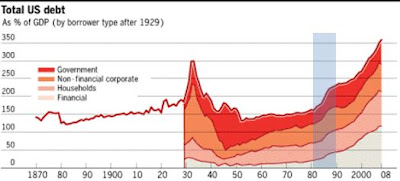

By autumn 1981, Thatcher started cutting interest rates. In the following year's budget, Thatcher increased public expenditure. With the high number of the unemployed, it was not surprising that inflation remained low. Oil prices were also moving downwards. More importantly, the British economy was increasing its money supply (see chart below from McKinsey). It should also be noted that the previous British governments since the World War II had to contend with high public sector debt. So they resorted to inflation to bring the share of public debt down to manageable level. Thatcher benefited greatly from her predecessors' efforts, enabling her to start pumping credit again, though this time using households and financial institutions to undertake the borrowings. This recovery and the euphoria from the Falklands war victory enabled Thatcher to retain her premiership in the 1983 election.

The impact of the inflation especially in the 1970s helped to whittle down the real value of debt. As seen in the chart below (again from McKinsey), debt or credit has always been on the increase. Any political leaders thinking of crimping the total credit growth are dangerously courting a total social breakdown. Only inflation could ameliorate a debt growth. Consequently, the inexorable rise in UK's total real debt level beginning from the Thatcher's administration can be attributed not in a small way to the low inflation conditions prevailing since then.

Since Thatcher's story has many interesting lessons for our bumbling EU politicians, we'll continue the second part of the story with the conditions leading to her downfall.