Thatcher had to get the unemployment rate down to provide evidence of success for her economic policies. The easiest way to achieve growth was to unleash credit but first, Friedman's monetarism theory of stable monetary growth had to be permanently ended. The Bank of England did its part by officially abandoning monetarism in 1986. The US government had already turned on the monetary tap in 1984, thus securing Reagan his second term.

Thatcher had to get the unemployment rate down to provide evidence of success for her economic policies. The easiest way to achieve growth was to unleash credit but first, Friedman's monetarism theory of stable monetary growth had to be permanently ended. The Bank of England did its part by officially abandoning monetarism in 1986. The US government had already turned on the monetary tap in 1984, thus securing Reagan his second term.

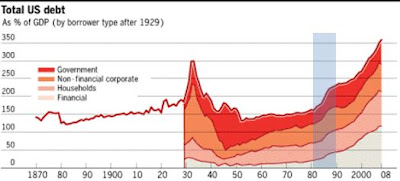

Unfortunately I've not been able to find the chart that plots the 1986 credit increase for the UK. The best that I've got is the earlier chart shown in Part 1 of this story which ends in 1985. Its follow-up chart (see below, also McKinsey's) however begins from 1987, leaving a gap for 1986. Regardless we can interpolate to find out what transpired in 1986. The UK's total credit as at end 1985 was slightly below 150% of GDP while that for (probably end) 1987 was 189 percent. So within two years, credit as a percentage of GDP grew by around 40 percent. That is a blistering pace that would have rocket-propelled any economy. The other thing about the chart that strikes the eye is the relentless growth in credit up until the onset of the current crisis. That strongly explains why Tony Blair, like Thatcher, also managed to hang on to three terms. One thing for sure, the successive British governments have been running the country into the ground as the price for keeping up with the major powers. The mess has now dropped into David Cameron's lap who is certain to be overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the total debt level.

Back to Thatcher, in her second term, she accomplished several noteworthy achievements. First she managed to break the back of the trade unions when the coal miners' union gave up their strike in March 1985. She also carried out large scale privatisation of nationalised industries. Estimates of the privatisation proceeds have ranged from £19 billion to £29 billion.

Her earlier privatisation of the nationalised industries and enfeeblement of the trade unions were expected to boost productivity which would unleash the goods supply to match the increased credit supply. This would also reduce unemployment just in time for the next election. Theoretically, that was how it should work but in reality, Britain's goods production had been severely impaired through neglect that the only growth for the economy was in the financial services and non-tradable real estate sectors. The eclipse of manufacturing was not entirely due to Thatcher's earlier contractionary monetary policy; the British firms had failed to invest at the same pace as Germany's or Japan's. Furthermore, Britain's petro economy had fostered a strong currency that remained so until early 1985, making exports non-competitive for its manufactured goods.

The credit growth that lasted from 1986 to 1990 was emblematic of Thatcher's trial-and-error experiment with the British economy. Her accomplice in this scheming was her Chancellor, Nigel Lawson who dismantled all financial barriers and regulations with the 1986 Big Bang. Lawson also brought down the basic tax rate from 30% in 1986 to 25% by 1988 and the top rate from 60% to 40%.

Thatcher and Lawson opened the gate for the foreign banks to set up shop in London much as the developing countries wooed the goods producers from the developed world to establish factories on their soil. It was hoped that financial services would take over from manufacturing as the country's biggest economic driver and turn London into a global financial centre. However, financial services could never replace the goods exports lost to the new manufacturing upstarts from Asia. The above chart from www.economicshelp.org proves that Britain has never been able to regain her manufacturing competitiveness that was lost way back in the early 1980s. It was estimated then that financial services exports would have to increase by 10% to make up for a 1% drop in manufactured goods exports.

Banking unlike manufacturing however is a very dangerous game. In manufacturing, during a recession, a major producer that packs up and closes shop will disrupt only the local supply chain and employment. In financial services, because of the widespread lending between financial institutions, a failure of a major bank can pull down the others unless the government steps in to take over the debts. This wholesale crash will cause the money supply to collapse and seize up the economy.

It is true that currently a large share of the assets, i.e., loans disbursed, of the British banks not only are made abroad but are also supported by borrowings from abroad: Table 9D of the Bank of International Settlement statistics as of 30 June 2011 shows that foreign banks' claims on UK borrowers amounted to US$3.06 trillion (second only to the US) while British banks' claims on foreign borrowers totalled US$4.18 trillion (biggest in the world). Regardless, the aphorism, attributed to J. Paul Getty, that when you borrow small, the problem is yours, but when you borrow big, the problem is the bank's, rings true for Britain's debt situation. Given this disproportionate dependency of the British economy on financial services (see how much the yawning current account goods deficit gap was closed by financial services in the above chart), Thatcher's promotion of financial services will in time come home to roost in the coming Grand Depression.

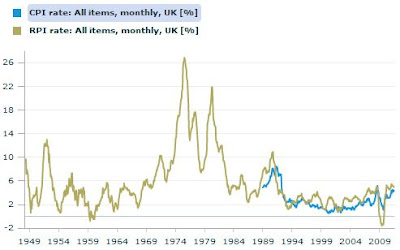

But Thatcher herself didn't have to wait for the coming Grand Depression. The quick-fix boost to the economy enabled Thatcher to be elected for a third term in 1987. Britain's house ownership at around 70% ranked among the world's highest, making the public eager voters for Thatcher's Conservative party. However the good times would soon be over, marking her third term as her downfall phase. The easy money had resulted in a capacity constraint that was followed by a surge in Britain's current account deficits and higher inflation (see chart above). To subdue inflation, the base rate was doubled from 7.5% in May 1988 to 15% by October 1989, bursting the housing bubble. Unemployment crept up to its pre-boom level. However inflation took two years after the peak of the interest rate hike, to be contained. Worse, with the oil prices still in the doldrums, Thatcher no longer had the luxury of oil wealth to appease the public with increased social security and unemployment benefits.

The trap had been set for Thatcher to stumble into. It just needed only a trigger. She survived the poll tax riots in March 1990. But the general unfavourable economic conditions made it tougher for her to ride roughshod over her Tory colleagues without creating deep animosity. They needed a bone to pick with her. Her strident stand against increasing European encroachment on Britain's sovereignty became their cause. Feeling that she might lose the second round of a leadership challenge, she voluntarily resigned her premiership in November 1990. What an ignominious exit, three consecutive wins at the polls, only to be stabbed in the back by party colleagues.

Had Thatcher restricted herself to two terms, like Reagan, she would have stepped down with her reputation held in high esteem. The British public would be now yearning for her leadership although in reality, she benefited largely from factors beyond her control, especially the oil wealth. Without its crutch, her downfall was predictably swift.